Like everyone else in Ireland, last month I watched the newly-launched trailer for Wild Mountain Thyme with my jaw on the floor as a parade of diddly-eye Irish clichés not seen since the dark days of Walt Disney’s 1959 leprechaun fantasy Darby O'Gill and The Little People was crammed into two-and-a-half minutes. Like the diaspora of Irish people living all over the world, my toes curled as dollops of synthetic paddywhackery followed broad cultural stereotype followed borderline national insult. Like anyone who has ever visited Ireland on holiday, or met an Irish person, I rubbed my ears in disbelief as our melodious native accent was mangled beyond recognition once again by an actor playing "Irish".

More like this:

– The worst depictions of Paris in film and TV

– Twelve films to watch in December

– The most demonised sequel of all time?

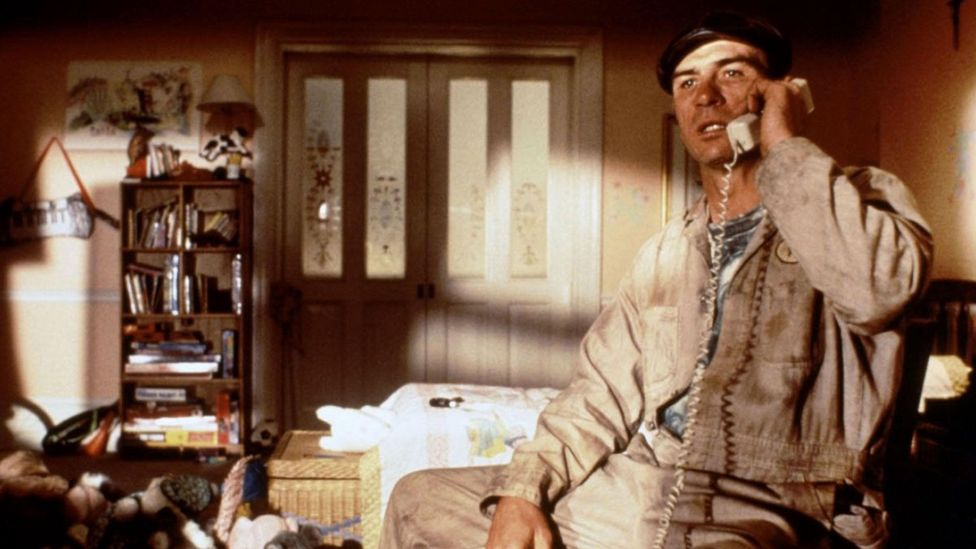

John Patrick Shanley's romantic comedy, shot last year in and around the very real town of Ballina, County Mayo, has Emily Blunt and Jamie Dornan as neighbouring farmers and star-cross'd lovers living in a luridly emerald Ireland scattered with thatched cottages, rocky roads and blow-dried and set livestock. We watch as Dornan's broth of a boy has a conversation with a nonplussed donkey in a crayon-green field while red-headed colleen Blunt pulls a tartan shawl around her shoulders and dances a jig in her Wellingtons. At one point, a man tumbles into a lake from a coracle (a type of ancient wicker canoe) while someone else genuflects in wonder before a fancy car, suggesting the film might be set some time between the Bronze Age and last St Patrick’s Day. An elderly man in a tweed flat cap sticks his head over a stone wall and cackles toothlessly at the antic goings-on. "I don’t understand you people," Jon Hamm’s Yank carpetbagger exclaims. Me neither, Jon.

Wild Mountain Thyme stars Emily Blunt and Jamie Dornan as neighbouring farmers and star-cross'd lovers living in a luridly emerald Ireland (Credit: Alamy)

Social media was quick to mock the wobbling Irish accents, with actual Irishman Dornan (from Holywood in County Down, as it happens) singled out for special ridicule. Then Irish-American writer and director John Patrick Shanley, who adapted the film from his own 2014 Broadway play, Outside Mullingar (itself based on summers he had spent with his Irish cousins in the titular midlands town) issued a huffy statement: "If my characters sounded exactly like my Irish relatives spoke, no one would understand them." The mockery only intensified. "Even we think this is a bit much," Ireland's National Leprechaun Museum said in a tweet.

"While remembering it's not fair to judge a film on its trailer, the accents are all over the place," admonishes Gerry Grennell, performance and dialogue coach at Dublin's Bow Street Academy for Screen Acting. "Things aren't helped by the writing, which is the same 'faith and begorrah, top o' the mornin', may the road rise to meet you' rubbish that was old hat in the 1940s. It's pretty dismal." However Grennell, who has helped Heath Ledger and Johnny Depp polish their respective brogues, still maintains the Irish are too thin-skinned when it comes to non-Irish actors attempting an Irish accent. "We have to get over ourselves, and I include myself in that. Global audiences are not looking at films made in or about Ireland for a perfect rendition of a native accent or an accurate reflection of the country. They're looking for connections in the story that mirror their own lives, wherever they might be watching from." They'll be watching from the US in the first instance, with the Bleeker Street production being released in selected cinemas and on streaming platforms there today – and many of the reviews so far have doubled-down on the advance ridicule. Indiewire's David Ehrlich says this "soda farl of banter and blarney couldn't be a broader caricature of Irish culture if it were written by the Keebler elves and directed by a pint of Guinness" while The A.V. Club critic Katie Rife notes that "the characterisations, motivations, dialogue, and acting in this film are all so clumsy and baffling that a bad regional inflection is just one sin among many."

What is 'Irishness'?

When depicting ethnicity and nationality on screen, there is a fine line between useful shorthands and reductive stereotypes. The French like wine, cheese and adultery, movies tell us, while Italians go in for tiny coffees and big hand gestures. It's all too easy to use broad cultural signifiers as sticks to trounce subtlety and nuance and Hollywood likes easy. All the clichés we have come to expect from American films set in Ireland are present and correct in the Wild Mountain Thyme trailer: wince-inducing accents that turn the simplest sentence into a lilting song, lashings of rain, astroturfed landscapes, slow-witted boyos and love-lorn girleens.

"Most stories told about Ireland are not for the Irish who live in Ireland, so 'Irishness' in Hollywood only serves the needs of those who will pay to see it. You're not obliged to. Unless you're teaching Irish cinema…" says Dr Harvey O'Brien, Assistant Professor of Film Studies at University College Dublin, who questions the idea that film-makers can faithfully portray some nebulous concept of 'Irishness' in the first place. "There are many varieties and shadings in what Ireland and the Irish stand for, and that’s often to do with context and setting, particularly in history. The idea that there is some primordial Irish 'authenticity' is a fallacy."

But our general sensitivities around how Irish characters are portrayed on screen, often by non-Irish actors, begs the question, in cinematic terms then, who are we? "It's the oldest question in the book. Several books, actually," O’Brien says. "Fundamentally, Irishness in Hollywood is still code for a certain kind of ancestral rural whiteness from which more advanced societies have evolved, but which is still perfectly preserved somewhere in the psychic museum."

John Ford’s 1952 film The Quiet Man, starring John Wayne and Maureen O'Hara, is Hollywood's quintessential Irish fantasy (Credit: Alamy)

Modern audiences might think the era of Irish economic prosperity in the last two decades would have inspired new paradigms in depicting the country internationally, to say nothing of the global success of Irish film-makers like Lenny Abrahamson, Aisling Walsh, and John Crowley, but the message of change has not reached Hollywood. In contemporary depictions of Irish characters in US cinema, we can still identify stereotypes established more than a century ago in vaudeville; the so-called Stage Irish archetype was an exaggerated caricature of supposedly Irish characteristics in speech and behaviour, "garrulous, boastful, unreliable, hard-drinking, belligerent (though cowardly) and chronically impecunious", as The Oxford Companion to Irish Literature puts it. Ireland and America have a long cross-fertilised history, but is that really how they still see us?

No conversation about depictions of Ireland on screen can avoid John Ford’s 1952 romantic comedy The Quiet Man, the cinematic ur-text of an imaginary Emerald Isle adapted from a short story originally written for an American magazine by the once hugely popular novelist Maurice Walsh. Set some time in the 1920s, the film tells the story of emigrant heavyweight boxer Sean, played by Ford's beloved side of beef John Wayne, who returns to the fictional village of Innisfree (actually Cong in County Mayo) from Philadelphia. Having made his fortune in the ring. Sean yearns to find love and peace and does so – eventually – in the arms of Maureen O'Hara's Mary Kate, sister of the swaggering local bully who covets the returning American's ancestral farm. As the two lovers squabble their way into each other's affections, Ford stages a climactic fist-fight between the warring men that takes them for miles over the mountain roads and across the bogs and back down through the town, scattering chickens and sheep to a knockout finish in the local pub, where foamy pints of Guinness help the unconscious loser back to his senses.

Breathlessly romanticised and expansively funny, the film was a smash, particularly among the Irish-American community. It won Ford his fourth Oscar for best director and the best box-office returns of his long career, while its success established a template for a postcard image of Ireland that was already 30 years out of date and 30 degrees removed from reality. Even at the time of its release, The Quiet Man was being cited as responsible for a significant increase in Irish-American tourism to "the old country" and the colourful, convivial agrarian past imagined through Ford’s Technicolor lens has left an enduring legacy. 2.4 million Americans visited Ireland in 2018, according to Tourism Ireland, the marketing body responsible for selling the country overseas, and spent a combined $1.6 bn. The Quiet Man museum in Cong, a perfect recreation of a cottage in the film that was in reality only ever a set on a Hollywood sound stage, is one of the busiest attractions in the region.

Visions of the 'old country'

"Ireland on screen is coded in history, poetry, greenery [and] simplicity and that’s just part of the image our tourist industry relies on to sell tradition and nostalgia for the imagined old country, particularly to Irish-Americans," says O'Brien, citing Ron Howard's sweeping 1992 melodrama Far and Away, starring Tom Cruise as a tenant farmer, as another movie clearly designed to appeal to Irish-Americans’ genealogical fantasies. "It opens in the lush Irish countryside long ago but quickly goes where the title tells us it is going and becomes a story about the building of America. Ireland and the Irish serve only as backdrop – the place where these new Americans came from, but not where they are any more." O'Brien wonders if there is a trade-off between the millions of euros foreign film productions bring to Ireland, and the tourism dollars that follow in their wake, and the ersatz depiction of Ireland they consolidate. "If we continue to sell an image of Ireland that applies only to sites and experiences designed to provide what is being sold, and take that money so we can live lives totally unlike the ones the tourists are buying, should we be racked with guilt? This isn’t a new question. We have always been happy enough to accept international investment at a cost to arguably outdated ideas of purity and authenticity."

In recent times, films like PS I Love You have fed into a stereotypical image of the Irish male as soulful and poetic (Credit: Alamy)

In the early days of cinema, the romantic vision of Old Ireland as a place riven with warring tribes, tutting priests, and mourning women certainly did more harm than good. By the 1920s, a decade in which 220,000 people left Ireland to settle in America, anti-Irish, anti-Catholic prejudice in the US was at its peak. How the Irish were depicted on the silver screen wasn't helping. "Back then we were fighters, gangsters, rebels or priests", says Dr Ruth Barton, Head of the School of Creative Arts at the Samuel Beckett Centre in Trinity College, Dublin. "Emigration and the long, painful legacy of colonialism are central to the Irish demand for recognisable portrayals of our identity on screen. It's not that long ago that we were fighting to take control of our own image and tell our own stories and we still take it badly when other people claim to speak on our behalf or try to claim our identities."

Barton cites the three phenomenally successful US tours mounted by Dublin's famed Abbey Theatre in the 1930s as central to a change in how Irishness was portrayed in American cinema. Criss-crossing the continent with a programme of plays by Sean O'Casey and John Millington Synge, the Abbey's leading man Barry Fitzgerald was persuaded to remain behind in Hollywood. A gifted character actor he quickly took his place in the pantheon, winning an Oscar for playing a wise old priest in 1944's Going My Way opposite an Irish-American, Bing Crosby, and directed by another, Leo McCarey. Icons followed: Jimmy Cagney, Maureen O’Hara, Pat O’Brien, Spencer Tracy, Maureen O’Sullivan, Gene Kelly, and Fitzgerald's favourite director John Ford, all either native born or second-generation Irish.

The kind of films this powerful new group made over the decades helped Depression-era Americans reassess their prejudices against Irish immigrants, not because of our good looks and twinkling charm, or at least not only because of them, but by offering ordinary Americans an escape to a simpler, more poetic place, far from the ruins of capitalism. Their popularity ultimately ended the ferocious anti-Irish, anti-Catholic animus that was a staple of American life well into the 1950s. "Americans who rejected Irish Catholics in politics embraced them in culture," observes Christopher Shannon in his book Bowery to Broadway: The American Irish in Classic American Cinema.

The ideal Irishman

These days, a particularly favoured Irish stereotype is that of the Irish male as a romantic ideal. "See the vulnerability of Liam Neeson in the first half of his career, before he turned into an unstoppable action hero, or Chris O'Dowd as the shy, solid police officer in 2011's Bridesmaids, or Gerard Butler’s character in the romantic drama PS I Love You," says Barton. In that latter hugely successful 2007 weepie, Hilary Swank is guided through life, and back to the grounding green fields of Ireland, by a trail of letters left by her dead Irish husband. It was followed three years later by Leap Year, which saw American Amy Adams chasing her boyfriend across the country because, according to the film's invented Irish tradition, she can propose marriage to him on the 29th of February and he must accept it, only to fall accidentally in love with Matthew Goode's dewy-eyed bartender instead. "These films are indicative of how our shared image of the Irish male has softened into something more soulful and poetic," says Barton, "but it is far more difficult to ascertain who the Irish woman is on screen. Saoirse Ronan almost never plays Irish characters, nor do Jessie Buckley or Ruth Negga. It's been a long time since a Technicolor Maureen O'Hara defined the Irish colleen as a feisty independent spirit."

The 1994 film Blown Away was part of a benighted 1990s subgenre of Hollywood thrillers centred on Irish terrorists (Credit: Alamy)

Barton sees the emergence of a vibrant, outgoing homegrown film industry over the last decades as an essential counterbalance to the international cinema that has used Ireland as a stage setting with grass. "I don't know that we are as sensitive as we used to be to Stage Irishness, since we now produce our own renowned films that reflect our society as it is, and speaks to us in our own voices, but there are some egregious Oirish stereotypes that deserve special mention." She is quick to name the film she believes to be the worst offender. "The 1937 Will Hay comedy Oh, Mr Porter! might be almost forgotten now but it was a smash hit in its day and is just a succession of impossibly clumsy clichés" she says, adding that the depiction of the Irish as wily peasants in Far and Away, garrulous ne'er-do-wells in Snatch (2000) and conniving hucksters in Waking Ned (1998) all fell into the same reductive traps set decades before.

And if the Irish haven't been playing windswept hunks or twinkling alcoholics, they have been seen pulling on balaclavas and planting bombs. The painful history of the Troubles and how it has been clumsily represented in Hollywood is a complex subject, but Barton says particular mention should go to the 1994 thriller Blown Away, in which Tommy Lee Jones portrayed a crazed Northern Irish bomber with an especially indecipherable, tongue-twister accent and a limited understanding of his own political aims. The film, a modest success, was part of a benighted 1990s subgenre of thrillers centred on Irish terrorists that included Sean Bean in 1992's Tom Clancy adaptation Patriot Games, repeat accent-offender Brad Pitt in The Devil's Own (1997) and a slow-blinking Richard Gere in the same year's The Jackal.

Grennell doesn't feel the need to list the advances the Irish film industry has made in recent decades in bringing a more realistic portrayal of a multi-faceted Ireland to international audiences. "If I had to do a roll call, we'd be here all day," he says. "The short version is that Ireland now punches well above its weight in global film: in acting, in writing, in directing, in music, and in all the technical aspects of cinema production. We've just chosen Tomás Ó Súilleabháin's Arracht, a hard-hitting Irish-language film about the Great Famine of the 1840s, to represent us at next year's Academy Awards. For 99% of the world Arracht will be a foreign language film so accent and dialect are immaterial. If the film is going to mean anything to an international audience it has to work emotionally. Wild Mountain Thyme is a very different proposition but it must make the same connection if it’s going to stop us from laughing at it, and make us laugh with it."

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

"Hollywood" - Google News

December 11, 2020 at 07:02AM

https://ift.tt/3741Bi6

Why Hollywood gets the Irish so wrong - BBC News

"Hollywood" - Google News

https://ift.tt/38iWBEK

https://ift.tt/3fdiOHW

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Why Hollywood gets the Irish so wrong - BBC News"

Post a Comment