“By gossiping about celebrities and by talking about what they’ve done that isn’t so great, it allows us to establish our values as a community and also for me, as an individual, to advertise my values to the people I’m speaking with,” says professor Julia Fawcett, who teaches a course called the History of Celebrity in the Department of Theater, Dance and Performance Studies.

Celebrities, one theory goes, act to unite imagined communities in a modern nation. When people used to know everyone in their villages, now we use celebrities to come together in a new kind of group. “I’m a fan of Beyoncé, and you’re a fan of Beyoncé, so now we’re a part of this imagined community,” says Fawcett.

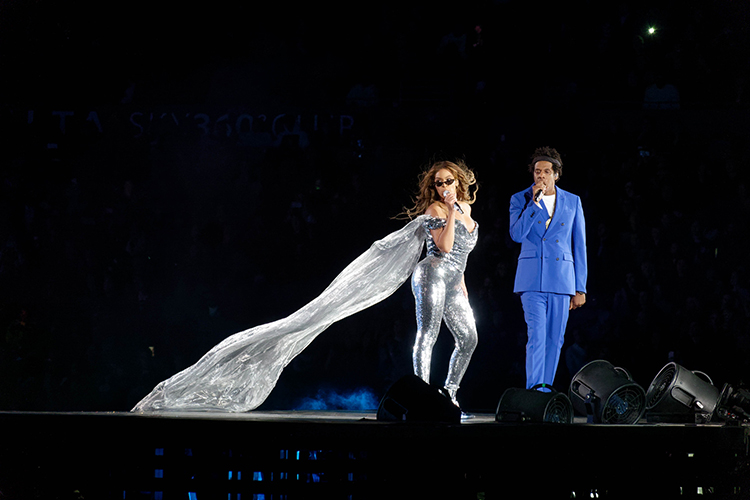

Beyoncé and Jay-Z perform together during their On the Run II tour in 2018. (Photo by Ronald Woan via Flickr)

Read a transcript of Fiat Vox episode #71: “How we create ‘imagined communities’ with celebrity gossip.”

Clip from Vogue’s “73 Questions with Selena Gomez”:

Interviewer: I’m so excited for this. Selena! I hope you’re ready for the 73 Questions interview.

Narration: Vogue has this video series called “73 Questions Answered by Your Favorite Celebs.” It’s shot in one take, and it’s supposed to give us a look into who celebrities really are. But they’re obviously very rehearsed.

[Music: “Highride” by Blue Dot Sessions]

There’s one with singer Selena Gomez, where she’s walking through her home.

Interviewer: Besides doing adventurous interviews like this, what do you do on your days off?

Selena Gomez: Hang out with my friends.

Narration: She pours the videographer a glass of orange juice, checks a text on her phone from her mom and plays some music. It’s had more than 34 million views.

Toward the end, the videographer says:

Interviewer: Can you tell me a secret?

Narration: And she says… wait for it…

Selena Gomez: I think I was born in the wrong era.

Julia Fawcett: (Laughs) That’s not helpful, I don’t care about that.

Narration: That’s Julia Fawcett. She’s an associate professor of theater, dance and performance studies at UC Berkeley. This semester, she’s teaching a class called the History of Celebrity.

Julia Fawcett, an associate professor in the Department of Theater, Dance and Performance Studies, teaches a course called the History of Celebrity. (UC Berkeley photo)

Julia Fawcett: One of the things that we’ve been talking about in class is the way that celebrities, to keep us buying magazines and to keep us looking, they have to somehow get away with promising us this secret private life that they’re going to reveal, but never actually reveal it. But still make us keep desiring it because we have to keep buying more magazines. Somehow they have to do it in a way that we don’t catch on. They keep promising us this, not giving it to us. And they do it again and again. We’re duped! I’m duped all the time by this.

Narration: But why do we want to know about them? What about celebrities makes them interesting to us? Are they just a frivolous fixation that helps us pass the time, or do they tell us something about our culture and who we are? Do they somehow fill a deeper need that we have?

These are some of the questions that Fawcett asks in class. And, obviously, she thinks there’s more to celebrity than many of us let on.

This is Fiat Vox, a Berkeley News podcast. I’m Anne Brice.

[Music fades]

So, what role might celebrities play in our lives? Fawcett says there are many theories. Here one:

Julia Fawcett: There’s a writer, Benedict Anderson, who has the theory of the imagined community. The imagined community basically means it used to be that we all lived in these little villages. And so, my identity was tied to my village, but that was easy to do because I knew all the other people in my village. But then, when we have the emergence of the modern nation, I don’t know everybody in my village anymore, right? I don’t know every single other American. And so, one of the ideas about celebrity is that it’s another way of forming an imagined community: I’m a fan of Beyoncé, and you’re a fan of Beyoncé, so now we’re a part of this imagined community.

Narration: Kellyann Ye is in the History of Celebrity course. She’s a senior double-majoring in computer science and theater and performance studies.

Kellyann Ye: I will say I feel like, if I have to make small talk with any college student, I could just start talking about John Mulaney.

Narration: John Mulaney is a comedian who talks a lot about his own life and experiences.

Kellyann Ye: Like at work — I’m a T.A. for CS class. We’ve had several post-work conversations about John Mulaney. We just sit and go, “Oh, yeah, John Mulaney.” And then someone starts quoting a bit. And then some people join in and quote the rest of the bit.

I feel like there’s a lot to say about humor and community, in general. Because the idea of getting the joke is like being part of sort of like an in-group.

Narration: As a teenager in the 2010s, Ye, who grew up in Sunnyvale, California, says she didn’t see many celebrities in mainstream media who looked like her.

Kellyann Ye: I’m Chinese American. That influences the way I consume all media. I remember thinking when Crazy Rich Asians and To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before came out, that if they had had that in middle school or high school, I would have talked about celebrity a lot more and I would have known actors. I would have seen actors doing films of the kind that I was interested in.

[Music: “Coulis Coulis” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Narration: Fawcett says that the importance of relatability comes up a lot in class. We often want to feel connected to the experiences and identities of the celebrities we choose to represent us.

And, she says, the growing importance of relatability also comes from how we consume celebrity culture today.

There’s one theory that Fawcett discusses in her class that says celebrities help us connect with other like-minded people. “I’m a fan of Beyoncé, and you’re a fan of Beyoncé, so now we’re a part of this imagined community,” says Fawcett. (Photo by thanassis 79 via Flickr)

Julia Fawcett: It’s not on a big screen in the movie theater, where it’s glamorous and, you know, we have close-ups. It’s now on our smartphones or on our computers.

Narration: We have access to celebrities in ways we didn’t used to. We can tweet to them and they can respond. We can follow them and tag them on Instagram and TikTok. We can watch videos of them talking directly to us on YouTube.

We see these bits and pieces of their lives, or at least what they show us of their performed lives.

Ye says she got a Twitter account a few years ago just so she could follow a favorite author of hers, Maggie Stiefvater, who wrote the fantasy novel The Scorpio Races, among other books.

Kellyann Ye: She just talked about her daily life on her blog and what she felt about what was happening in her life, and it was fascinating to me. I was just like, “You’re a published writer and you’re a woman. That could be me.”

Narration: But we haven’t always wanted celebrities to be relatable, says Fawcett. Throughout history, celebrities have played a different kind of role. They were valued more for their glamour and fabulousness, for their otherworldly charisma that set them apart from the rest of us.

Some theorists say that celebrities reminded us of God — except they were tangible and accessible, people who we could see just walking down the street.

This idea that celebrities served a kind of divine purpose goes back to England in the 18th century, when many believe the concept of celebrity was born.

Julia Fawcett: One of the theories about where celebrity comes from religion and kings, essentially. We used to have a god that would unite entire nations — theoretically, would unite entire nations, although it never quite worked out that way — but that was the idea. Or a king or queen would unite an entire nation by making laws, but also by being this arbiter of values and this kind of spectacular thing that we could all look at and say, “I know I’m English because I see myself as the subject of Queen Elizabeth. And I can identify with you because you also see yourself as a subject of Queen Elizabeth.”

And so, one of the theories that we’ve been thinking about in class, and that I think is really compelling, is that celebrity emerged when democracy did, because suddenly the king became less important, the people became more important, and so, celebrities emerged to take over that spectacular role of the king, whereas the democratic leaders took over the role of the king as a maker of laws.

Narration: So, when we talk about celebrities, we’re actually talking about our values. It’s not about if Jay-Z cheated on Beyoncé. It’s about what we think about that and what that says about us.

Julia Fawcett: That’s my way of saying to my friends, “One of my values is that you don’t cheat on your wife or you don’t cheat on your significant other.” And so, by gossiping about celebrities and by sort of talking about what they’ve done that isn’t so great, that also allows us to establish our values as a community and also for me, as an individual, to advertise my values to the people I’m speaking with.

[Music: “Vernouillet” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Narration: Celebrities are famous for all different reasons. Some for their remarkable talents and others just for being famous.

But, Fawcett says, all celebrities can offer us insight into ourselves and what we value as a society.

Julia Fawcett: I think that the humanities, for so long, was about finding what was good — finding the art that was good or the literature that was good. And, of course, people had very exclusive definitions of what counted as good literature. And it meant excluding a lot of people and a lot of stories that were important to tell.

And so, I’m excited that one of the things that we’ve started to ask more in the humanities is not, “What is good?” but “Why do people like this?” Or, “Why is this popular?” Because I think that’s actually a question that tells us a lot more about ourselves than “What do we think is good?”

Narration: This is Fiat Vox, a Berkeley News podcast. I’m Anne Brice, a podcast producer for the Office of Communications and Public Affairs.

You can subscribe to Fiat Vox, spelled F-I-A-T V-O-X, wherever you listen to podcasts. And if you have a moment, give us a rating on Apple Podcasts — it really helps bring more visibility to the work we do. And if you enjoyed this episode, consider sharing it with a friend. It’s a great way to get the word out.

Also, check out our other podcast, Berkeley Talks, which features lectures and conversations at UC Berkeley. You can find all of our podcast episodes on Berkeley News at news.berkeley.edu/podcasts.

Listen to other episodes of Fiat Vox:

"celebrities" - Google News

March 17, 2021 at 03:20AM

https://ift.tt/3vAkC6a

How we create 'imagined communities' with celebrity gossip - UC Berkeley

"celebrities" - Google News

https://ift.tt/3bWxE3n

https://ift.tt/3fdiOHW

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "How we create 'imagined communities' with celebrity gossip - UC Berkeley"

Post a Comment